|

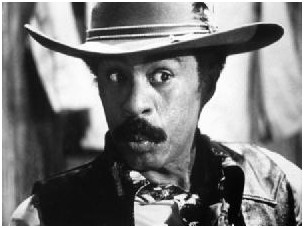

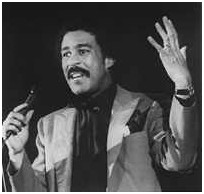

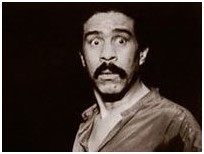

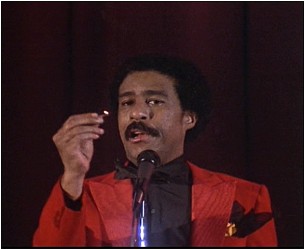

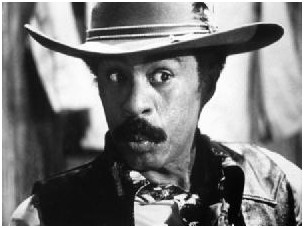

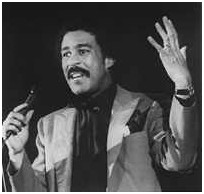

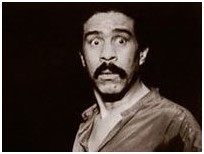

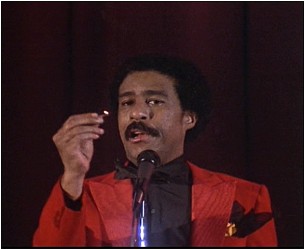

Actor-comedian Richard Franklin Lennox Thomas Pryor III (December 1, 1940 – December 10, 2005), who helped transform comedy with biting commentary on race and his own shortcomings, died on Saturday

of cardiac arrest at the age of 65 in Encino, California. He was pronounced dead at a local hospital at 7:58 a.m. Pacific Time on December 10, 2005. He was brought to the hospital after his wife's attempts to resuscitate him failed. His wife was quoted as saying "at the end, there was a smile on his face."

Actor-comedian Richard Franklin Lennox Thomas Pryor III (December 1, 1940 – December 10, 2005), who helped transform comedy with biting commentary on race and his own shortcomings, died on Saturday

of cardiac arrest at the age of 65 in Encino, California. He was pronounced dead at a local hospital at 7:58 a.m. Pacific Time on December 10, 2005. He was brought to the hospital after his wife's attempts to resuscitate him failed. His wife was quoted as saying "at the end, there was a smile on his face."

"He was my treasure," Jennifer Pryor said in a telephone interview. "His comedy is unparalleled. They say that you are not a comic unless you imitate Richard Pryor. ... He was able to turn his pain into comedy."

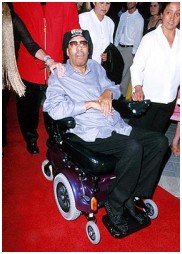

Pryor's wife said he died of cardiac arrest at 7:58 a.m. PST after her efforts to resuscitate him failed and after he was taken to a hospital in the Los Angeles suburb of Encino. Pryor had been suffering from multiple sclerosis, a degenerative nervous system disease, for almost 20 years.

He's been so strong for so many years," Jennifer Pryor told CNN. "He's had this disease (multiple sclerosis) since 1986 ... He's had beyond nine lives. We used to joke he's going to outlive everybody.

"He was an extraordinary man, as you know. He enjoyed life right up until the end. He did not suffer, he went quickly, at the end there was a smile on his face ... he's a very, very, very amazing man and he opened doors to so many people."

"He had a courage and a heart and a spirit that was unmatchable and, of course, he was controversial," Jennifer Pryor said. "That was wonderful Richard. He told the truth, didn't he? ... he told the truth and he was very proud.

"Bigoted rednecks came up to Richard and told him, 'Thank you for opening my eyes,' because he was so in touch with the truth and only spoke the truth ... people respond to that."

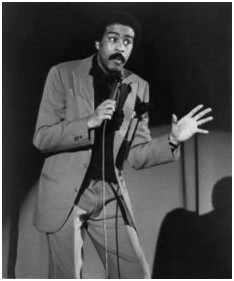

A gifted storyteller known for unflinching examinations of race and custom in modern life, Pryor shattered many barriers for American stand-up comedians such as Dave Chappelle, Robin Williams, Eddie Murphy, Chris Rock, Arsenio Hall, David Letterman, and others. Though he frequently used colorful language, vulgarities, as well as racial epithets, he reached a broad audience with his trenchant observations. Pryor was often ranked among the best stand-up comedians, although he rarely got his due among American audiences because he was too controversial.

Pryor was at his best when he took the tragic events that happened during his life and made them a part of his onstage routine in concert movies and recordings such as "Richard Pryor: Live & Smokin'" (1971), "That Nigger's Crazy" (1974), "Bicentennial Nigger" (1976), "Richard Pryor: Wanted – Live In Concert" (1979) and "Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip" (1982).

Early life and career

Born in 1940 in Peoria, Illinois, Pryor grew up in his grandmother's brothel. While growing up the whorehouse, Richard was subjected to seeing his mother prostituting herself. His mother, Gertude died when Richard was 27 years old. His father, LeRoy Pryor (a.k.a. Buck Carter) was a bartender, boxer, and World War II veteran, who died in 1968 when Richard was 28. From 1958-1960, Pryor served in the U.S. Army. He was one of the few African Americans living in the Midwest in the 1940s.

Born in 1940 in Peoria, Illinois, Pryor grew up in his grandmother's brothel. While growing up the whorehouse, Richard was subjected to seeing his mother prostituting herself. His mother, Gertude died when Richard was 27 years old. His father, LeRoy Pryor (a.k.a. Buck Carter) was a bartender, boxer, and World War II veteran, who died in 1968 when Richard was 28. From 1958-1960, Pryor served in the U.S. Army. He was one of the few African Americans living in the Midwest in the 1940s.

His first professional performance came at age 7, when he played drums at a night club. Early in his career, Pryor was a more middlebrow, nonthreatening comic in the Bill Cosby tradition. The first five tracks on the 2005 compilation CD Evolution/Revolution: The Early Years (1966-1974), recorded in 1966 and 1967, capture Pryor in this embryonic stage.

In September 1967, Pryor had what he called in his autobiography Pryor Convictions an "epiphany" when he walked onto the stage at the Aladdin Hotel in Las Vegas (with Dean Martin in the audience), looked at the sold-out crowd, said over the microphone "What the **** am I doing here!?", and walked off the stage. Afterward, Pryor began working at least mild profanity and the word nigger into his act. His first comedy recording, the eponymous 1968 debut release on the Dove/Reprise label, captures this particular period, not long after that breakdown.

Mainstream success

In 1969 Pryor moved to Berkeley, California, where he immersed himself in the counterculture and rubbed elbows with the likes of Huey P. Newton and Ishmael Reed. He signed with the comedy-centric independent record label Laff Records in 1970 and recorded his second album, Craps (After Hours). Not long afterward, Pryor sought a deal with a larger label, and after a protracted period of time, signed with Stax Records. His third, breakthrough album, That Nigger's Crazy, was released in 1974 and, Laff, who claimed ownership of Pryor's recording rights, almost succeeded in getting an injunction to prevent the album from being sold. Negotiations led to Pryor being released from his Laff contract in exchange for the small label being allowed to release previously unissued material, recorded between 1968 and 1973, at their leisure.

In 1969 Pryor moved to Berkeley, California, where he immersed himself in the counterculture and rubbed elbows with the likes of Huey P. Newton and Ishmael Reed. He signed with the comedy-centric independent record label Laff Records in 1970 and recorded his second album, Craps (After Hours). Not long afterward, Pryor sought a deal with a larger label, and after a protracted period of time, signed with Stax Records. His third, breakthrough album, That Nigger's Crazy, was released in 1974 and, Laff, who claimed ownership of Pryor's recording rights, almost succeeded in getting an injunction to prevent the album from being sold. Negotiations led to Pryor being released from his Laff contract in exchange for the small label being allowed to release previously unissued material, recorded between 1968 and 1973, at their leisure.

During the legal battle, Stax briefly closed its doors. Pryor then re-signed with Reprise/Warner Bros., who immediately rereleased That Nigger's Crazy on the heels of his first album under his new Reprise/Warner Bros. deal, ...Is It Something I Said?. With every successful album Pryor recorded for Warner Bros. (or later, his concert films and his 1980 free-basing accident), Laff would quickly publish a hastily-compiled, badly-packaged album of old material to capitalize on Pryor's growing fame - a practice the label would continue until 1983.

Comfortably successful and into the zenith of his career, Pryor visited Africa in 1979. Upon returning to the United States, Pryor swore he would never use the "N" word in his stand-up comedy routine again. (His favorite epithet, "mother******", remains a term of endearment on his official website to this day.)

Comfortably successful and into the zenith of his career, Pryor visited Africa in 1979. Upon returning to the United States, Pryor swore he would never use the "N" word in his stand-up comedy routine again. (His favorite epithet, "mother******", remains a term of endearment on his official website to this day.)

In 1983 his status as a major worldwide star was confirmed when he signed a five year contract with Columbia pictures for $40,000,000.

Pryor appeared in several popular films including Lady Sings the Blues, The Mack, Uptown Saturday Night, Silver Streak, Which Way Is Up?, Car Wash, The Toy, Superman III (which earned Pryor $4,000,000), Brewster's Millions, Stir Crazy, Moving, See No Evil, Hear No Evil and Blue Collar. In four of his films, he co-starred with Gene Wilder. Though he made four films with Gene Wilder, the two comic actors were never as close as many thought according to the latter's autobiography.

He also co-wrote Blazing Saddles directed by Mel Brooks and starring Gene Wilder. Pryor was to play the sheriff in "Blazing Saddles", but the film's producers were unsettled by his vulgarity and Mel Brooks chose Cleavon Little instead, although Pryor still co-wrote the script. Before his infamous 1980 free-basing accident, Pryor was about to start filming Mel Brooks' History of the World, Part I. Pryor was replaced at the last minute by Gregory Hines. Pryor was also originally considered for the role of Billy Ray Valentine on Trading Places (1983), before Eddie Murphy ultimately won the part. Of particular note is The Toy, known equally as being one of Jackie Gleason's last projects.

The freebasing incident and its aftermath

On June 1, 1980, Pryor set himself on fire while freebasing cocaine. Pryor made this part of his heralded "final" stand up show "Richard Pryor Live On Sunset Strip" (1982). After joking that the incident was actually caused when he dunked a cookie into a glass containing two different types of milk, he gave a poignant yet both funny and serious account of his accident and recovery, then poked fun at people who told jokes about it by waving a lit match and saying "What's this? It's Richard Pryor running down the street." Interviewed in 2005, Jennifer Lee Pryor said that Richard poured high-proof rum over his body and torched himself in a drug psychosis. In a TV interview during his recovery Pryor said that he tried to commit suicide. His management created the "accident" lie for the press in hopes of protecting him.

On June 1, 1980, Pryor set himself on fire while freebasing cocaine. Pryor made this part of his heralded "final" stand up show "Richard Pryor Live On Sunset Strip" (1982). After joking that the incident was actually caused when he dunked a cookie into a glass containing two different types of milk, he gave a poignant yet both funny and serious account of his accident and recovery, then poked fun at people who told jokes about it by waving a lit match and saying "What's this? It's Richard Pryor running down the street." Interviewed in 2005, Jennifer Lee Pryor said that Richard poured high-proof rum over his body and torched himself in a drug psychosis. In a TV interview during his recovery Pryor said that he tried to commit suicide. His management created the "accident" lie for the press in hopes of protecting him.

He didn't stay away from live stand-up too long, though - in 1983 he filmed and released a new concert film and accompanying album, Here And Now, which he directed himself. He then wrote and directed a fictionalized account of his life, Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling.

In 1986, Pryor announced that he suffered from multiple sclerosis. In response to giving up drugs and alcohol after being diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, he said: "God gave me this M.S. shit to save my life." In 1992 he gave some final live performances, excerpts of which appear on the ...And It's Deep Too! box set. He continued to make occasional film appearances, pairing with Wilder one last time in the unsuccessful 1991 comedy, Another You (in which his physical deterioration was noted by many critics). His final film appearance was a small role in the David Lynch film Lost Highway in 1997.

Later life

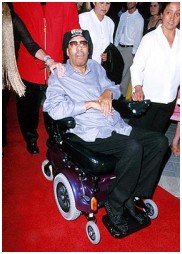

In his later years, Richard Pryor was confined to a wheelchair due to multiple sclerosis. In late 2004 his sister claimed that Pryor lost his voice. However, on January 9, 2005, Pryor himself rebutted this statement in a post on his official website, where he stated, "Sick of hearing this shit about me not talking... not true... good days, bad days... but I still am a talkin' mother******!"

In his later years, Richard Pryor was confined to a wheelchair due to multiple sclerosis. In late 2004 his sister claimed that Pryor lost his voice. However, on January 9, 2005, Pryor himself rebutted this statement in a post on his official website, where he stated, "Sick of hearing this shit about me not talking... not true... good days, bad days... but I still am a talkin' mother******!"

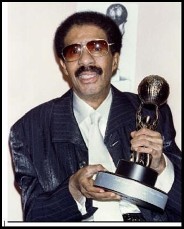

In 1998, Pryor won the inaugural Mark Twain Prize for American Humor from the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. According to Former Kennedy Center President Lawrence J. Wilker, "Richard Pryor was selected as the first recipient of the new Mark Twain Prize because as a stand-up comic, writer, and actor, he struck a chord, and a nerve, with America, forcing it to look at large social questions of race and the more tragicomic aspects of the human condition. Though uncompromising in his wit, Pryor, like Twain, projects a generosity of spirit that unites us. They were both trenchant social critics who spoke the truth, however outrageous."

In 2000, Rhino Records remastered all of Pryor's Reprise and Warner Bros. albums for inclusion in the box set ...And It's Deep Too! The Complete Warner Bros. Recordings (1968-1992).

In 2002, Pryor and his wife/manager Jennifer Lee Pryor, won the legal rights to all of the Laff material - almost 40 hours of reel-to-reel analog tape. After going through the tapes and getting Richard's blessing, Jennifer Lee Pryor gave Rhino Records access to the Laff tapes in 2004. These tapes, including the entire Craps album, form the basis of the double-CD release Evolution/Revolution: The Early Years (1966-1974).

In 2003, a television documentary, Richard Pryor: I Ain't Dead Yet, #*%$#@!!, came out. It consisted of archival footage of Pryor's performances and testimonials from fellow comedians such as Dave Chappelle, Wanda Sykes and Denis Leary of the influence Pryor had on comedy.

In 2004, Pryor was voted #1 of Comedy Central's 100 Greatest Standups of All Time[2]. In a 2005 British poll to find The Comedian's Comedian, Pryor was voted the 10th greatest comedy act ever by fellow comedians and comedy insiders.

Until his death, Pryor and his family were avid supporters of animal rights and the anti-vivisection movement. Pryor once offered a $1,000 reward for the arrest of the person who drowned dogs in Nahant, Massachusetts. Links to groups he supports can be found on his official website.

Personal

Richard Pryor was married seven times to five different women:

Patricia Price (1960 - ?) (divorced) 1 child

Shelly Bonus (1967 - 1969) (divorced) 1 child

Deborah McGuire (22 September 1977 - 1979) (divorced) 1 child

Jennifer Lee (August 1981 - October 1982) (divorced)

Flynn Belaine (October 1986 - January 1987) (divorced)

Flynn Belaine (1 April 1990 - ?) (divorced)

Jennifer Lee (June 2001 - 10 December 2005) (his death)

During his relationship with actress Pam Grier, Pryor proposed to actress, Deborah McGuire (1977).

He had seven children: Renee, Richard Jr, Elizabeth, Rain, Stephen, Kelsey, and Franklin Mason

Discography

Richard Pryor (Dove/Reprise, 1968)

Craps (After Hours) (Laff Records, 1971, reissued 1993 by Loose Cannon/Island)

That Nigger's Crazy, (Partee/Stax, 1974, reissued 1975 by Reprise)

...Is It Something I Said?, (Reprise, 1975, reissued 1991 on CD by Warner Archives)

Bicentennial Nigger, (Reprise, 1976)

L.A. Jail, (Tiger Lily, 1977)

Are You Serious???, (Laff, 1977)

Who Me? I'm Not Him, (Laff, 1977)

Black Ben The Blacksmith, (Laff, 1978)

(The title track was first issued as "Prison Play" on Richard Pryor, in spite of Warner Bros.' ownership of that particular master recording)

The Wizard Of Comedy, (Laff, 1978)

Wanted/Richard Pryor - Live In Concert (2-LP set), (Warner Bros., 1978

Outrageous, (Laff, 1979)

Insane, (Laff, 1980)

Holy Smoke!, (Laff, 1980)

Rev. Du Rite, (Laff, 1981)

Live On The Sunset Strip (Warner Bros., 1982)

Richard Pryor Live! (picture disc), (Phoenix/Audiofidelity, 1982)

Supernigger, (Laff. 1983)

Here And Now, (Warner Bros., 1983)

Filmography

The Busy Body (1967)

Uncle Tom's Fairy Tales (1968) (unfinished)

Wild in the Streets (1968)

The Black Brigade (1970)

The Phynx (1970)

You've Got to Walk It Like You Talk It or You'll Lose That Beat (1971)

Dynamite Chicken (1972)

Lady Sings the Blues (1972)

The Mack (1973)

Wattstax (1973) (documentary)

Hit! (1973)

Some Call It Loving (1973)

Uptown Saturday Night (1974)

The Lion Roars Again (1975) (short subject)

Adios Amigo (1976)

Car Wash (1976)

The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings (1976)

Silver Streak (1976)

Which Way Is Up? (1977)

Greased Lightning (1977)

Blue Collar (1978)

The Wiz (1978)

California Suite (1978)

Richard Pryor: Live in Concert (1979) (documentary)

The Muppet Movie (1979) (cameo)

Wholly Moses (1980)

In God We Tru$t (1980)

Stir Crazy (1980)

Bustin' Loose (1981)

Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip (1982) (documentary)

Some Kind of Hero (1982)

The Toy (1982)

Superman III (1983)

Richard Pryor: Here and Now (1983) (documentary)

Richard Pryor: Live and Smokin' (1985) (documentary)

Brewster's Millions (1985)

Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling (1986) (also director and co-writer)

Critical Condition (1987)

Moving (1988)

See No Evil, Hear No Evil (1989)

Harlem Nights (1989)

The Three Muscatels (1991)

Another You (1991)

A Century of Cinema (1994) (documentary)

Mad Dog Time (1996)

Lost Highway (1997)

Bitter Jester (2003) (documentary)

I Ain't Dead Yet, #*%$#@!! (2003)

|

Actor-comedian Richard Franklin Lennox Thomas Pryor III (December 1, 1940 – December 10, 2005), who helped transform comedy with biting commentary on race and his own shortcomings, died on Saturday

of cardiac arrest at the age of 65 in Encino, California. He was pronounced dead at a local hospital at 7:58 a.m. Pacific Time on December 10, 2005. He was brought to the hospital after his wife's attempts to resuscitate him failed. His wife was quoted as saying "at the end, there was a smile on his face."

Actor-comedian Richard Franklin Lennox Thomas Pryor III (December 1, 1940 – December 10, 2005), who helped transform comedy with biting commentary on race and his own shortcomings, died on Saturday

of cardiac arrest at the age of 65 in Encino, California. He was pronounced dead at a local hospital at 7:58 a.m. Pacific Time on December 10, 2005. He was brought to the hospital after his wife's attempts to resuscitate him failed. His wife was quoted as saying "at the end, there was a smile on his face." Born in 1940 in Peoria, Illinois, Pryor grew up in his grandmother's brothel. While growing up the whorehouse, Richard was subjected to seeing his mother prostituting herself. His mother, Gertude died when Richard was 27 years old. His father, LeRoy Pryor (a.k.a. Buck Carter) was a bartender, boxer, and World War II veteran, who died in 1968 when Richard was 28. From 1958-1960, Pryor served in the U.S. Army. He was one of the few African Americans living in the Midwest in the 1940s.

Born in 1940 in Peoria, Illinois, Pryor grew up in his grandmother's brothel. While growing up the whorehouse, Richard was subjected to seeing his mother prostituting herself. His mother, Gertude died when Richard was 27 years old. His father, LeRoy Pryor (a.k.a. Buck Carter) was a bartender, boxer, and World War II veteran, who died in 1968 when Richard was 28. From 1958-1960, Pryor served in the U.S. Army. He was one of the few African Americans living in the Midwest in the 1940s. In 1969 Pryor moved to Berkeley, California, where he immersed himself in the counterculture and rubbed elbows with the likes of Huey P. Newton and Ishmael Reed. He signed with the comedy-centric independent record label Laff Records in 1970 and recorded his second album, Craps (After Hours). Not long afterward, Pryor sought a deal with a larger label, and after a protracted period of time, signed with Stax Records. His third, breakthrough album, That Nigger's Crazy, was released in 1974 and, Laff, who claimed ownership of Pryor's recording rights, almost succeeded in getting an injunction to prevent the album from being sold. Negotiations led to Pryor being released from his Laff contract in exchange for the small label being allowed to release previously unissued material, recorded between 1968 and 1973, at their leisure.

In 1969 Pryor moved to Berkeley, California, where he immersed himself in the counterculture and rubbed elbows with the likes of Huey P. Newton and Ishmael Reed. He signed with the comedy-centric independent record label Laff Records in 1970 and recorded his second album, Craps (After Hours). Not long afterward, Pryor sought a deal with a larger label, and after a protracted period of time, signed with Stax Records. His third, breakthrough album, That Nigger's Crazy, was released in 1974 and, Laff, who claimed ownership of Pryor's recording rights, almost succeeded in getting an injunction to prevent the album from being sold. Negotiations led to Pryor being released from his Laff contract in exchange for the small label being allowed to release previously unissued material, recorded between 1968 and 1973, at their leisure. Comfortably successful and into the zenith of his career, Pryor visited Africa in 1979. Upon returning to the United States, Pryor swore he would never use the "N" word in his stand-up comedy routine again. (His favorite epithet, "mother******", remains a term of endearment on his official website to this day.)

Comfortably successful and into the zenith of his career, Pryor visited Africa in 1979. Upon returning to the United States, Pryor swore he would never use the "N" word in his stand-up comedy routine again. (His favorite epithet, "mother******", remains a term of endearment on his official website to this day.) On June 1, 1980, Pryor set himself on fire while freebasing cocaine. Pryor made this part of his heralded "final" stand up show "Richard Pryor Live On Sunset Strip" (1982). After joking that the incident was actually caused when he dunked a cookie into a glass containing two different types of milk, he gave a poignant yet both funny and serious account of his accident and recovery, then poked fun at people who told jokes about it by waving a lit match and saying "What's this? It's Richard Pryor running down the street." Interviewed in 2005, Jennifer Lee Pryor said that Richard poured high-proof rum over his body and torched himself in a drug psychosis. In a TV interview during his recovery Pryor said that he tried to commit suicide. His management created the "accident" lie for the press in hopes of protecting him.

On June 1, 1980, Pryor set himself on fire while freebasing cocaine. Pryor made this part of his heralded "final" stand up show "Richard Pryor Live On Sunset Strip" (1982). After joking that the incident was actually caused when he dunked a cookie into a glass containing two different types of milk, he gave a poignant yet both funny and serious account of his accident and recovery, then poked fun at people who told jokes about it by waving a lit match and saying "What's this? It's Richard Pryor running down the street." Interviewed in 2005, Jennifer Lee Pryor said that Richard poured high-proof rum over his body and torched himself in a drug psychosis. In a TV interview during his recovery Pryor said that he tried to commit suicide. His management created the "accident" lie for the press in hopes of protecting him. In his later years, Richard Pryor was confined to a wheelchair due to multiple sclerosis. In late 2004 his sister claimed that Pryor lost his voice. However, on January 9, 2005, Pryor himself rebutted this statement in a post on his official website, where he stated, "Sick of hearing this shit about me not talking... not true... good days, bad days... but I still am a talkin' mother******!"

In his later years, Richard Pryor was confined to a wheelchair due to multiple sclerosis. In late 2004 his sister claimed that Pryor lost his voice. However, on January 9, 2005, Pryor himself rebutted this statement in a post on his official website, where he stated, "Sick of hearing this shit about me not talking... not true... good days, bad days... but I still am a talkin' mother******!"