|

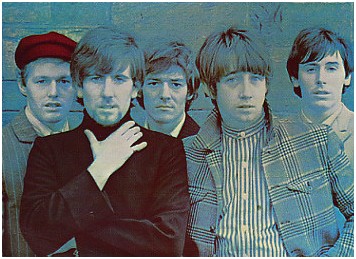

The Hollies have notched up over thirty hits since 1963 as one of the best and most commercially successful pop/rock acts of the British Invasion. When the Hollies began recording in 1963, they relied heavily upon the R&B/early rock & roll covers that provided the staple diet for countless British bands of the time. They quickly developed a more distinctive style of three-part harmonies (heavily influenced by the Everly Brothers), ringing guitars, and hook-happy material, penned by both outside writers (especially Graham Gouldman) and themselves, eventually composing most of their repertoire on their own. The Hollies had a squeaky-clean image, and were famous for their rich vocal harmonies, which rivalled those of The Beach Boys. The best early Hollies records evoke an infectious, melodic cheer similar to that of the early Beatles.

Like a lot of long-lived creative endeavors, The Hollies' history began by chance, in this case, five-year-old Allan Clarke's arrival as a new student one day at the Ordsall Primary School in Manchester, England in 1947.

Harold Allan Clarke was born April 5, 1942 in Salford, one of six children. He made the acquaintance of five-year-old Graham Nash (born February 2, 1942) on his first day at school, when Nash was the only student to volunteer to let Clarke sit next to him in class. The two became friends then and there, and it turned out that one of the interests they shared was music. They both sang in choir, joining their voices together for the first time in "The Lord Is My Shepherd," and it was from there that the notion of their singing together took root. They found that, even as they matured, their voices complemented each other magnificently. Unfortunately, there was no such thing as rock 'n' roll at the time, and their spontaneous musical efforts together didn't begin until the 1950s.

In 1956, everything changed, as rock 'n' roll began to trickle in to England from America, but the immediate impetus for Clarke and Nash to begin music careers together lay in the birth of skiffle music, with Lonnie Donegan and his version of "Rock Island Line," and its various follow-ups.

"We didn't know what hit when skiffle came along," Clarke observed. "We all wanted to be rock 'n' roll stars, and skiffle was one way to start, because it was all based on the easiest chords to play, A, D, G, and C, and we loved the songs. Graham and I played clubs in Manchester, doing an Everly Brothers-type thing. The Everly Brothers were our real inspiration, because of the two-part harmonies."

They worked under a variety of names, including the Two Teens and the Levins. The Levins, in particular, symbolized important breakthroughs in Clarke's mind, at least at the time, because the name was derived from the brand of guitars they were using, and simply having a brand of guitar that didn't make one ashamed was progress. "The Levins were named after my first jumbo guitar. I was very pleased with that at the time," he recalled in a 1996 interview.

With help from their families, Clarke and Nash purchased Guytone guitars, and re-christened themselves the Guytones, which later became the Fourtones.

Clarke and Nash played any place that anyone would listen to them, and this included a performance at the legendary Two I's coffee bar in London, where acts such as Tommy Steele and the Vipers (featuring future Shadows lead guitarist Hank B. Marvin) were discovered, and Cliff Richard played and sang. "It was years and years and years before we were a group," Clarke recalled of the Two I's, adding that it had little mystique for him, being a miserably tiny little place compared to locales such as the Cavern in Liverpool.

At one point, when it seemed like sibling acts such as the Everly Brothers were the coming thing, Clarke and Nash billed themselves as Ricky and Dane Young (Clarke was Ricky and Nash was Dane), hoping to be taken for a brother act. Such strategies would work better for real-life and fake siblings alike, such as the Brook Brothers and the Walker Brothers, not to mention the Righteous Brothers. But the Ricky and Dane Young gambit paid off, getting them hooked up for a time with a local Manchester band called the Fourtones, whose membership included Derek Quinn, later of Freddie and the Dreamers.

It was while they were playing a gig with the Fourtones that Clarke and Nash were approached by Eric Haydock (born Feb. 3, 1943), the bassist for a group called the Deltas, and invited to join his band. After abandoning the Fourtones, they took up Haydock's offer and signed aboard his band. The Deltas were a large ensemble group whose stage act included novelty songs and costume changes, none of which seemed to offer much of a future in the band scene as it was developing in Manchester and other points north.

Following a few membership and repertory changes, the Deltas provided the nucleus around which The Hollies formed. The new group, not yet named, featured Allan Clarke on lead vocals, Graham Nash on rhythm guitar and vocals, Eric Haydock on bass (rather unusually, a six-string model, incidentally, as opposed to the usual four), Vic Steele on lead guitar and Don Rathbone on drums.

How the new band got its name has been a subject of conjecture for decades, and stories are sufficiently vague to convince one that not even the band members remember exactly. The conventional assumption for many years was that Hollies was chosen as a tribute to Buddy Holly, in much the same manner that the Beatles chose their name as a sort of acknowledgment of the Crickets. But the truth was a little more uncertain.

The group members all admired Buddy Holly, to be sure, as did virtually every rock 'n' roller in England during this period. But the most likely reason for the choice of the name The Hollies was pure expediency and sheer luck, not admiration of Buddy Holly. According to one oft-told story which seems to have the kernel of truth within it, the group had been assembled out of the Deltas at the end of 1962, as the holidays were approaching, and were busy trying to decide upon a name in a room that happened to be heavily decorated with, among other Christmas-related accoutrements, holly. The band name followed, initially as a stop-gap, and it's stuck for 34 years and counting.

The band's first gig as The Hollies took place at the Oasis Club in Manchester in December 1962, and was a great success. Not long after, the Beatles graduated from the Cavern Club, having been signed to EMI's Parlophone label by producer George Martin, and soon after, The Hollies took their place at the most celebrated music venue in all of England.

At the time, the Liverpool quartet had barely scraped the charts with their debut single, "Love Me Do," but something was in the air in the north of England. The amount of musical activity in Liverpool and Manchester, coupled with the mere fact that Parlophone, a tiny label in the EMI family scarcely known for its acumen with popular music (the label's biggest releases until then were comedy records by Peter Sellers and Bernard Cribbins), had reached the Top 20 with a song by a Liverpool band, caused record producers who'd previously never ventured very far from London to start looking to the north.

One of them was Ron Richards, a staff producer at EMI, who went up to the Cavern in January 1963, just a few weeks after The Hollies were formed and shortly after they'd taken over the Beatles' spot at the Cavern, playing the mid-day shows. What he found was a tiny club that lived up (or down) to its name, packed to the rafters with teenagers jammed in as tight as they could, listening to this group wail away.

He also found that The Hollies could do more than just wail. They played fast and hard, because one just didn't compete in that environment without doing that--Richards was especially impressed with the furious manner in which Graham Nash attacked the fretboard on his guitar, until he learned that there were no strings on the instrument--but so did a lot of other bands on the Liverpool scene. Indeed, groups such as the Big Three, a northern power trio that held their fans in awe for a time, were considered far more formidable musically than either the Beatles or The Hollies.

But The Hollies, like the Beatles, the Searchers and a relative handful of bands working in those days, could also sing--and, like the Beatles, the Searchers et al, The Hollies could do more than just thump out a song with a pile-driver beat if that was what was needed. And as record producers soon discovered, that was exactly what was needed to put these acts over on record, as opposed to the clubs. Clarke and Nash could sing, and they could harmonize together, and the seemed to offer the possibility that they might be able to move beyond the American rock 'n' roll standards that they were learning off of the original records at the time.

Not all of this was necessarily obvious to Richards at the time. What was clear was that the group put on a good show, had charisma on stage, and offered at least as much potential as the Beatles seemed to at the time. He invited the group to come to London for an audition for EMI's Parlophone label. The acceptance of this invitation led to the first split in the primordial ranks of The Hollies, as guitarist Vic Steele bowed out, preferring not to turn professional.

The group's manager, Alan Cheetham, began scouting a replacement in one Tony Hicks (born December 16, 1945), who was making a name for himself locally as an ax-man with a band called Ricky Shaw and the Dolphins. The Dolphins' drummer was Bobby Elliott (born December 8, 1941), who would later become the final link in The Hollies' success. At that time, however, Elliott was more concerned with losing a talented band mate to a rival group.

"I remember this guy used to turn up at every gig," he recalled in February 1996, of Cheetham's efforts, "and we knew he was trying to get Tony away from us!"

Tony Hicks was, even then, a guitarist's guitarist, one of the most skilled players in a field filled with many would-be stars but relatively few genuine, viable talents. His own entry into music came by way of skiffle music, which he loved. He was drawn to the guitar early on, and his first instrument, an acoustic model, came to him by the kindness of an aunt who purchased it for him. Early on, he knew what he wanted to do with music and what he wanted to play. This, in turn, only heightened his fixation on American rock 'n' rollers, because they had better players and better guitars than almost anything available in England at the time.

Hicks was born too late to have seen Buddy Holly play in England, but he is old enough to remember the ads for Holly's shows. Holly and other American guitarists, most notably Rick Nelson's lead player, James Burton, fascinated him. "I remember hearing 'Hello Mary Lou,'" he recalled in an interview early in 1996, "and wondering who was playing that wonderful guitar."

In those days, he recalled, this was not a lonely fixation. "Concerts would sell out just because of the guitars that these bands were playing," he remembered. "We would travel to the shows just to get a look at the guitars."

Hicks's first group was a skiffle band named, appropriately enough, Les Skifflelets, which, he recalled, was a bunch of guitars, all playing rhythm, one board and one bass. As with most skiffle bands, the members generally drifted off gradually into other activities as they discovered the limits of their abilities or, as in Hicks's case, they remained in music and began expanding those limits. His own early guitar idols included Big Jim Sullivan, James Burton and Chet Atkins, but not--perhaps not surprisingly, in view of these preferences--Chuck Berry. "I was more into Eddie Cochran," he recalled, of rock 'n' roll's first wave.

Eventually, Hicks's musical sensibilities took him in a very specific direction, through his experience of the legendary English band Johnny Kidd and the Pirates. "I was 14 or 15 when I saw them, playing ballrooms," he remembered of the group, who were responsible for writing and having the first hit with "Shakin' All Over," generally acknowledged as the first piece of genuinely top-grade rock 'n' roll to come out of England. "There was Johnny Kidd, and this three-piece band, and they were just incredible to hear, they played so loud and clean. That was the sound that I wanted on stage--just one guitar, one bass, and drums, with no rhythm guitar in the way."

Ricky Shaw and the Dolphins was a popular local act, and despite Cheetham's entreaties to consider joining The Hollies, Hicks wasn't about to give up a spot in his group to join and band barely 60 days old. At the time, Hicks remembered in an early 1970s interview, the band scene in the north was one of healthy competition, but not necessarily the frenzied rivalries portrayed in the press. "I think it was just good press news to make the north--Liverpool, Manchester and whatever--out to be that. Fierce? I don't know.

"There was competition, inasmuch as there were groups equally as good as each other. There was no jealousy. I must admit that the Liverpool groups come more to mind. As far as Liverpool goes, top of the tree was the Beatles, and then you move down with Gerry and the Pacemakers, Billy J. Kramer and then names that didn't particularly make it, the Remo Four and the Big Three. They stick out in my mind more than Manchester. We'd play at the Cavern and just wander out and see the Big Three play, which was just incredible. It was something very new, very exciting. Old amplifiers, no sophisticated stuff. I remember the guitarist with the Big Three [Brian Griffiths] used to go onstage with four strings. He'd go out and play with four strings. They were just rough and ready Liverpool geezers, there for a few pints. And he'd think 'four strings? Fair enough. Better than three, but I'd prefer five or six.'"

Hicks decided to check The Hollies out, and went to one of their shows. He liked what he heard, and was given more to think about when he learned from Graham Nash of Ron Richards's offer of an EMI audition.

Hicks then decided to play a rehearsal with the group, and their run-through of a handful of songs satisfied everyone, and he was in the band. The EMI audition took place on April 4, 1963 at EMI's Abbey Road Studio No. 2, which led to three finished songs, a cover of the Coasters' "(Ain't That) Just Like Me," and two originals by Allan Clarke and Graham Nash, "Hey What's Wrong With Me," and "Whole World Over." "(Ain't That) Just Like Me," completed in 10 takes, became the band's debut single, released at the beginning of May 1963 backed with "Hey What's Wrong With Me."

During the week of May 25, 1963, musical acts of all descriptions occupied the 50 places on the British record charts. The Beatles were at #1 with "From Me To You" and ex-Shadows Jet Harris and Tony Meehan were at #2 with an instrumental entitled "Scarlett O'Hara." Scattered across the rest of the British Top 50 were songs by transplanted Scotsman Johnny Cymbal ("Mr. Bass Mann"), the Springfields ("Island Of Dreams"), featuring Dusty Springfield in her folk music phase, and Sweden's spacesuit-clad rock 'n' roll loonies, the Spotnicks, among others.

Ensconced some 49 places down from the Beatles' single that same week was Parlophone R5030, "(Ain't That) Just Like Me," a debut recording by The Hollies. Eventually it would rise to #25, a modest but respectable first showing, and probably comparable to what the Beatles' "Love Me Do" would have done had Brian Epstein not helped cook the record books by purchasing a couple of thousand copies through his NEMS Record Shop.

The group followed this up with another Coasters cover, "Searchin'," recorded July 25, 1963 in 13 takes, with one of the band's managers, Tommy Sanderson, playing the piano. It was released the following month, with the B-side, "Whole World Over," another Clarke-Nash original, appropriated from the April 4 session. This record did decidedly better, entering the charts on August 29, 1963, and eventually peaking at #12 in England. Naturally, in this prior to the Beatles' arrival in America, there was no U.S. release of either record, nor any consideration of an American issue. These were records conceived and sold entirely to a local and national market, though by the time of "Searchin'," with the Beatles on their third #1 single, it was becoming clear to everyone that there was real money and fame to be had for musicians from the north of England, at least in England.

It was just after the recording of "Searchin'" that another line-up change in The Hollies took place, as drummer Don Rathbone left the band. "I think Don Rathbone left the band," Clarke said, "because he wasn't that good a drummer, and it was becoming obvious from our recordings."

Rathbone, who hailed from Stoke-on-Trent, left the band in the late summer of 1963 to go into management, before leaving the music business. His replacement was virtually waiting in the wings, Hicks's old Dolphins' band mate Bobby Elliott, who had moved on from the Dolphins to playing with Shane Fenton (who later emerged in the 1970s glitter scene as Alvin Stardust) and the Fentones.

The classic Hollies line-up was now in place. Elliott's arrival was more than a little fortuitous, for not only was Elliott--whose personal musical interests went more toward jazz than rock 'n' roll--one of the best drummers on the band scene in the north of England, but he had a good ear for songs and music in general. In later years, when The Hollies were going through musical and membership transitions that left their stage act a little less than tight, his playing would impart a laser-like focus to more than one concert. But more immediately, in the early fall of 1963, his and Tony Hicks's discovery of an old copy of "Stay" by Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs, unearthed at a junk shop in Scotland, gave the band the source for its third single.

The October 11, 1963 session yielded a proper single in only eight takes (the band was getting better in the studio), and the November 1963 release charted immediately and became their first Top 10 success, rising to #8 in England. The B-side was a Clarke-Nash leftover from a May 1963 session with Rathbone still on drums, "Now's The Time."

As a sign of the times, it became their first single to be released in America. By the late fall of 1963, some U.S. record companies were becoming aware that there was something stirring in England that could, although it was unlikely, catch on in America as well. "Stay" was the first Hollies record to benefit from these vague indications of interest in British rock 'n' roll, making its first appearance on this side of the Atlantic in January 1964, courtesy of a contract with Imperial Records negotiated by Ron Richards and Tommy Sanderson.

By that time the Beatles' records were showing up in the States, along with a handful of other British releases. The Hollies' "Stay" was part of that handful, and it never charted in America, a situation with which the group would become familiar over the next year or two. The Hollies' relationship with Imperial would later prove frustrating, but at the time simply getting their records out in America was a breakthrough.

The Hollies' fourth single, "Just One Look," was another cover, this time of an original by American singer Doris Troy that was first heard by the band at a party. "It just stood out as a great song," Tony Hicks remembers. The song was to become the earliest track by The Hollies that most Americans would know.

Recorded on January 27, 1964 and released the following month, "Just One Look" was the record that established The Hollies once and for all as hit-makers, rising to #2 in England. In America, however, it barely scraped the charts, edging to #98 for a week, but the British success was still significant, a breakthrough for the band, and also gave a special benefit to Tony Hicks and Bobby Elliott. Up to this time, all of The Hollies' B-sides had been written by Allan Clarke and Elliott, who benefited as songwriters from the success of the A-side--the authors of a single's B-side collecting royalties on the same basis as the authors of the A-side. For the B-side of "Just One Look," however, at Ron Richards' urging, Hicks and Elliott delivered their one and only collaboration as songwriters, in the form of "Keep Off That Friend Of Mine."

The singing on "Just One Look" was the finest The Hollies had committed to vinyl up to this time, with radiant harmonies and a powerful, soulful lead vocal performance by Clarke, crisp guitar playing, and drumming by Bobby Elliott that also managed to stand out amid all of this activity, with Eric Haydock providing a melodic yet rock solid performance at the bottom of it all on the bass. It was probably the classic, perfect record by the early Hollies, showing them off to best advantage, reshaping an American song in their image. "Keep Off Of That Friend Of Mine," by contrast, didn't reveal Hicks and Elliott as great unheralded songwriting talents, but it did give Hicks one of his best guitar showcases on record from this era.

By this time, The Hollies were firmly established in the front rank of British beat boom bands, with a respectable record of success and a formidable stage act. Clarke's, Nash's and Hicks's voices were among the best in the business, and the instrumental trio of Hicks, Haydock and Elliott was like a steamroller on stage, flattening much of the local competition. A number of their early tours put them alongside acts like the Rolling Stones, where they held their own. By rights, the band should have been a sensation in the press as well, but somehow The Hollies were not accorded the kind of respect and attention that their northern peers--Gerry and the Pacemakers and the Searchers (the Beatles by then having no equals, in terms of success or exposure)--received.

The group's problem was two-fold. The first lay in its image, which was somewhat indistinct--the group's only "gimmick" was its incredible harmonies, which somehow didn't make as good copy as the silly dance steps of their Manchester compatriots Freddie and the Dreamers, or the overbearing cuteness of the likes of Herman's Hermits. And somehow, Searchers spokesperson Chris Curtis was always being printed saying something deemed quotable, and Searchers bassist Tony Jackson was also treated as something of a "star" within the group, while The Hollies were seldom written up at all.

The other problem rested with the way their work was perceived by the more serious critics and listeners. The Hollies were already "suspect" for the prettiness and upbeat nature of their work, which made them seem like nothing more than a pop outfit. They might've gotten past that problem however, if only a successful songwriter or two had emerged from their ranks very early on, as the Beatles had.

But The Hollies' songwriting efforts were confined to the B-sides of their singles, and showed off the limitations of their abilities in this area. As it was, their fifth single, "Here I Go Again," was to feature an original (credited to "Chester Mann," as in Manchester) that had a very high haunt count in its verses and melodies, but it was just not considered enough. And as long as The Hollies specialized in covering established hits from America, they were going to have a credibility problem with more serious critics and listeners.

Their first album, Stay With The Hollies, released in January 1964, the same month that they recorded "Just One Look," consisted entirely of covers and only seemed to exacerbate their problem. The fact that each of their first four singles were covers of American R&B, and two of them specifically songs by the Coasters, had alienated some listeners.

Naturally, all English bands of the era did their own covers of some American R&B, and if all a group was interested in was potential chart action, that was no problem--a record either sold or it didn't. But the Beatles and, even more so, the Rolling Stones and the Animals, succeeded separating the sheep from the goats with their R&B covers. John Lennon's larynx-tearing performance on the Beatles' version of "Twist And Shout," and the group's only slightly less impassioned versions of "Please Mr. Postman," "You've Really Got A Hold On Me" and "Long Tall Sally"; the Stones' cranked-up, high-voltage renderings of Chuck Berry's "Come On" and the Valentinos' "It's All Over Now"; and the Animals' definitive cover of "House Of The Rising Sun" (which they got from a record by Josh White, not Bob Dylan, as has long been reported)--all of these records raised the ante for any other British groups seeking to interpret American songs and get good press for it on top of good sales.

The Hollies got the latter, but not always the former. That dubious arbiter of British taste, Screaming Lord Sutch, reviewing the group's single "Searchin'," in the August 31, 1963 Melody Maker, wrote: "I can't describe how much I hate it. It's a complete muck up of a great R&B thing. Horrible when you know the original. This record is absolutely diabolical. I loathe it and I hope it flops." Fortunately, the British public didn't share his disdain, and "Searchin'" did sell.

To be taken seriously as well as sell records, however, a band had to do more than just pleasant or lively covers of American songs. To some onlookers, it was unclear at first just what The Hollies were trying to do with their covers, become ballsier competitors to Freddie and the Dreamers, or players in the bigger leagues, alongside the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

Allan Clarke felt compelled to respond to this in the February 22, 1964 issue of Melody Maker: "[We do covers of American songs] because we like doing them, we think they sound good, and we do them our own way. We're not comparing ourselves with the Coasters but just the same we've done two of their numbers."

More recently, Clarke still maintained, "They were simply good songs, and we did them differently."

Still, the bookings poured in, regardless of the critics, and the band was working harder than ever. In April 1964, the band embarked on a seven-week tour of England booked in support of the Dave Clark 5, then riding the wave of success generated by their early hits.

The group's fifth single, "We're Through," was their first original A-side, written by Allan Clarke, Tony Hicks and Graham Nash under their new collective pseudonym of "L. Ransford." The song garnered a favorable Melody Maker (September 12, 1964) critique from Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones, appearing as a guest reviewer in the magazine's "Blind Date" column, in which a celebrity was asked to comment on new recordings without being told whose record it was.

Recorded on August 25, 1964, "We're Through" was released the following month, paired off with an original B-side, the somewhat harder rocking "Come On Back," and on September 26, 1964, the single entered the British charts at No. 27 and, during a relatively short stay, peaked at #7, a fact that, in the wake of "Just One Look's" #2 showing, discouraged the record company from pursuing any more original A-sides from the band at that time. As an original A-side, however, it was a milestone for the band, and portended better things to come for them.

In January 1965, the group returned to outside sources with a new single, Gerry Goffin and Russ Titelman's "Yes I Will," which was brought to the band's attention by producer Ron Richards from a demo on which Goffin's then wife Carole King was singing. The record, cut in 16 takes on January 3, 1965, had a more elegant sound than their previous singles, with more sophisticated playing and singing. It was strongly reminiscent of the Beatles, the Roulettes and the Merseybeats, except perhaps more elegant in its singing than anything those groups would have achieved. The B-side, the "L. Ransford" original "Nobody," recorded in two takes during a December 15, 1964 session, was a somewhat bluesier than usual number, complete with a dominant harmonica--played by Allan Clarke, who did all of the harp on The Hollies' records--and a raunchy guitar sound for a change.

"Yes I Will" reached #9 on the British charts, and by this time, it was clear that The Hollies had staying power among the first wave of post-Beatles British Beat bands. Unlike some of the other first wave bands, whose popularity had reached a plateau or begun to recede--or which could only maintain their audience with the heaviest of publicity pushes--The Hollies' audience was not only consolidating but growing, and each single marked a new step forward, an experiment with a slightly different instrumental sound or vocal arrangement. Moreover, they were doing it without a huge amount of publicity--the band was not mentioned much in the music press during those early days.

By the spring of 1964 in England, the shine was beginning to wear off the so-called Merseybeat sound and the bands specializing in it, and it was clear that a lot of groups that had sold records with relatively little effort up to that point were going to face an increasingly competitive musical environment. The Hollies were staying ahead of the curve, continuing to evolve as a recording act, and outclassing their competition onstage. In March 1965, with "Yes I Will" still ensconced at #11 on the charts, the group began its biggest tour of England yet, booked with the Rolling Stones.

Interviewed in Melody Maker on March 27, 1965, Hicks explained the difference between the group's live and studio sound, which mostly involved the guitars. "We don't use a rhythm guitar onstage--we think they blur the sound, get in the way. I'm happy to say a lot of people, including Americans, have complimented us on our clean instrumental sound. I believe this is why."

Indeed, the group's records in some ways sold it short in terms of its sound onstage, which was far more powerful than the singles would have indicated. Onstage, the group resembled acts such as Johnny Kidd and the Pirates, and Screaming Lord Sutch's Savages, as much as it did the Beatles, Hicks's guitar and Eric Haydock's bass, coupled with Elliott's drumming, making up one of the tightest, loudest instrumental ensembles this side of the Who.

Hicks also placed himself in a somewhat conservative light in the same article, separating himself from Keith Richards's comments in the same piece about lessons not being necessary for a would-be guitarist. "Unlike Keith Richard, I do believe in budding guitarists having lessons. I took two years of classical guitar lessons, and I still find them helpful."

In April of that year, The Hollies made their first visit to the United States, a week-long engagement at the Paramount Theater in Brooklyn, on a bill hosted by comic Soupy Sales and starring Little Richard, among others. During this same visit, they also made their first appearance on the network music showcase Hullabaloo.

By 1965, the Hollies were established as one of Britain's pre-eminent singles bands. In 1966, they also began to enjoy huge chart success in many other countries, as well. The band released a string of classic harmony-pop hits including "Bus Stop" (US #5 - 1966) written by future 10CC member Graham Gouldman, "Look Through Any Window" (US #32 - 1966), "Stop Stop Stop" (US #7 - 1966), "Carrie Anne" (US #9 - 1967) from which actress Carrie-Anne Moss got her name having been born when the song was on the charts), "On A Carousel" (US #11 - 1967), "Pay You Back With Interest" (US #28 - 1967) and "Jennifer Eccles" (US #40 - 1968).

When Graham Nash, one of the group's main songwriters, left in 1968 over creative differences, he joined forces with former Buffalo Springfield member Stephen Stills and ex-Byrds member David Crosby to form one of the first supergroups, Crosby, Stills and Nash. Soon afterwards, a massive audition took place for a suitable successor. Guitarist-singer Terry Sylvester of the Swinging Blue Jeans eventually joined. This lineup had an immediate UK hit with "Sorry, Suzanne." The same year The Hollies hit the UK charts at #3 with the emotional ballad "He Ain't Heavy, He's My Brother" (US #7 - 1970) whose recording featured the piano playing of Elton John.

Singer Allan Clarke briefly left the group in 1971 for a solo career. European star Mikael Rickfors overcame language barriers as Clarke's replacement, yielding the minor hit "The Baby." Clarke returned in 1972 with the Creedence Clearwater Revival-inspired smash hit, "Long Cool Woman in a Black Dress" (US #2 - 1972) and the Top 40 hit "Long Dark Road" (US #26).

The Hollies last visited the US top ten in June of 1974 with the soaring, grandiose love song "The Air That I Breathe" (US # 6 - 1974) which brought comparison of the group's successful vocal style to The Everly Brothers as well as to The Beatles. Unlike some other British Invasion bands The Hollies were also accomplished in concert, as indicated by their 1977 Hollies Live album, which included effective performances of lesser-known songs such as Hicks' working-class portrayal "Too Young to be Married" as well as the expected hits.

The band continued to record and tour sporadically in various lineups through the mid-1980s, last hitting the US top 40 with a remake of The Supremes' "Stop! In The Name Of Love" (Us # 29 - 1983).

Three of the core members, drummer Bobby Elliott, lead singer Allan Clarke and lead guitarist Tony Hicks continued to perform as the Hollies until April 2000, when Clarke announced that due to personal reasons he was retiring from the touring incarnation of the group. He was replaced by Carl Wayne, former lead singer of The Move. Wayne stayed with the Hollies until his death from cancer in August 2004.

After Wayne's death, Peter Howarth became the lead singer. Like Graham Nash, Peter was born in Blackpool and has been singing with his boss, Cliff Richard, for fifteen years. From his very first performance with The Hollies in Germany in October 2004, his vocal style instantly authenticated those famous Hollies harmonies.

Throughout 2005, the band has been hard at work recording an album of brand new songs. This project is important and exciting. In fact the boys have postponed a Summer Tour of The United States so they can concentrate wholly on the album; although the band will perform at previously planned prestigious summer festivals and concerts in Europe and England.

The Album will feature a host of major song writing talent from both sides of the Atlantic and is scheduled for release in February 2006. Several songs are penned by Rob Davis, who along with The Hollies´ Ray Stiles, was a founder member of the British band MUD.

|